Three related posts that have hung around for too long, so much so that I’ve been tempted to ditch them as being out of date and of relatively little interest. They were supposed to be three short posts. They’ve grown. There’s a lesson there…

In part, this extended (and extending) tinkering is due to my recent acquaintance with a glorious Victorian: the Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould (1834-1924). What a fascinating, multifaceted, contradiction of a man he sounds. I could happily devote an entire post to him. Instead I’ll restrict myself to a few facts that made me smile. He was a hagiographer and an antiquarian; a novelist, a folk song collector and a collector of tales, myths and legends. An eclectic scholar in fact – and a composer of hymns. As well as his day job as an Anglican priest.

Well-heeled and well-travelled, he was a devoted Devonian and he loved the West Country, especially Dartmoor which was close to his family home. One of his grandsons, William Stuart Baring-Gould, wrote a fictional biography of Sherlock Holmes, and based Holmes’ childhood on that of his grandfather. And Sabine himself appeared as a character in Laurie R King’s The Moor, a Holmesian pastiche. He is presented as Sherlock’s godfather.

He met his wife-to-be when she was 14 years old. He was a young curate; she was the daughter of a mill hand. His then vicar arranged for her to live with relatives in York to learn ‘middle class manners’. They were married for 48 years until her death and produced 15 children.

On her tombstone, Baring-Gould had inscribed:

Dimidium Animae Meae

“Half my Soul”

His best known hymn, incidentally, is Onward, Christian Soldiers.

Try as I might, I struggle to conflate the man who wrote that hymn with the man who revealed his heart on his wife’s tombstone.

Rev. Baring-Gould came into my orbit as the writer of A Book of Dartmoor, published in 1900: a copy of which lies next to me courtesy of the reserve store of the Cornwall Library system. And he’s now on my list of guests I would love to invite to dinner. That being unlikely to happen in the near future, I’ll content myself with quoting from his eclectic tome.

Beginning with useful advice on bogs, which is found in the earliest chapter in his book. Clearly he was anxious to forewarn the unwary traveller:

On the hillsides, and in the bottoms, quaking-bogs may be lighted upon or tumbled into. To light upon them is easy enough, to get out if one tumbled into (sic) is a difficult matter. They are happily small, and can at once be recognised by the vivid green pillow of moss that overlies them. This pillow is sufficiently close in texture and buoyant to support a man’s weight, but it has a mischievous habit of thinning around the edge, and if the water be stepped into where this fringe is, it is quite possible for the inexperienced to go under, and be enabled at his leisure to investigate the lower surface of the covering duvet of porous moss. Whether he will be able to give to the world the benefit of his observations may be open to question.

Just as well perhaps, that the moor was too wet to allow tramping across the rocks and gullies when we were there in January. Instead we took to the road, but on foot, which gave us a strong feel for the open vistas from the safety and solidity of tarmac.

Not ideal, but good enough. After all, what can you expect in January? We had not expected anything to be open either: much of the West Country closes down in these early months of the year.

However, our information folder at the hotel mentioned the museum attached to Dartmoor Prison as being open every day. It’s the sort of place that would interest Bernie. Regretfully, the information wasn’t quite accurate: the museum is open every day apart from in January, when it’s not open at all.

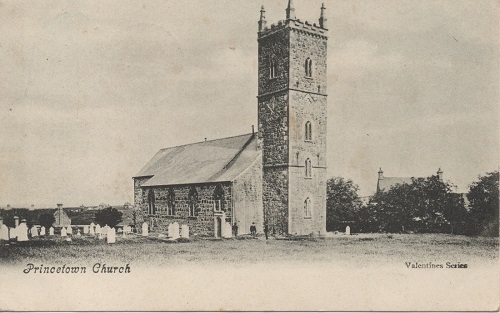

This we learned having firstly tramped to Princetown – a long, grey and unassuming little town; and having secondly tramped around the perimeter and finally past the prison itself – already at the far end of town and austere in the extreme. The Reverend includes several anecdotes concerning escape attempts and seems almost on the side of the prisoners, but he is clearly not keen on Princetown. When it comes to describing the town his sense of humour lets him down:

It is on the most inclement site that could have been selected, catching the clouds from the south-west and condensing fog about it when everywhere else is clear. It is exposed equally to the north and east winds. It stands over fourteen hundred feet above the sea, above the sources of the Meavy, in the ugliest, as well as least suitable situation that could have been selected.

I really don’t think it’s as bad as he makes it sound. And fortunately for us, all was not lost. As we stood in the damp churchyard, studying the gravestones and contemplating the walk back, a breathless young lady rushed up bearing an impressive ring of keys. She thought her husband had already unlocked the church, she told us, and he had thought that she had done it. Either way, the door was now open. We hadn’t planned to go in but it seemed rude not to after her efforts. And it’s good to know that not everything closes down in January.

Two wars: one church

This is the header on the leaflet of The Church of St Michael and All Angels.

The only church in England to have been built by French and American Prisoners of War.

Bernie grasped it immediately; it took me a while before I understood which wars we were talking about and began to make the connections between the church, the town and the prison. My interest was piqued.

In 1805, there were thousands of prisoners from the Napoleonic Wars housed on ‘hulks’ – derelict ships off the coast of Devon. Conditions were appalling and there were concerns at the proximity to the Royal Naval Dockyard. It was decided to rehouse the prisoners in a remote PoW depot isolated in the middle of Dartmoor. It took three years to build and the first prisoners arrived in 1809. This is a wild, exposed site – open to the elements and enduring high winds and more than twice the national average rainfall. Sabine’s dour view of the area is shared by others: it has been variously described as “unquestionably the bleakest place in Devon”. We were there in January: I promise you, it really isn’t that bad! Things have definitely improved over the last hundred years! But I begin to see why the site was chosen: it was the prison that came first.

The church was built to serve the prison and the community that grew around it, and was intended to house a congregation of five to six hundred. Built from local granite, it was to be a frugal construction, although the original plans were sent back, deemed to be too frugal. A proper bell tower was added. Initially built using the labour of Napoleonic prisoners of war; they were replaced by American prisoners from the war of 1812 and then by a further influx of French prisoners. The prison closed as the final batch of men were released in 1816, and the church – only recently completed – was closed too. After all that work.

In 1831, as the local population increased, it was re-consecrated. The prison was reopened in 1850 as a convict prison: providing the good reverend with his escapology material. And for a time the church flourished, only to suffer a major fire in 1868 and the steady erosion caused by the severe Dartmoor weather. In 1994 the decay was such that the Church could no longer afford its upkeep and the building was made redundant. It is now a listed building under the care of the Churches Conservation Trust. The church is still consecrated and is still occasionally used for services. When we were there it felt warm and welcoming, and gave every appearance of being in regular use. It felt very much like a living part of the community.

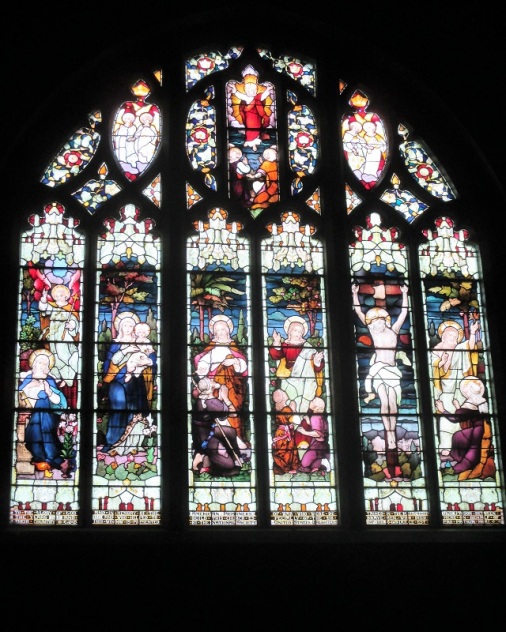

A great deal of work has been done to preserve this unique building, with support from the Daughters of the American Revolution, who raised funds for the beautiful stained-glass East Window which was was installed in 1910 in memory of the American prisoners who helped to build the church.

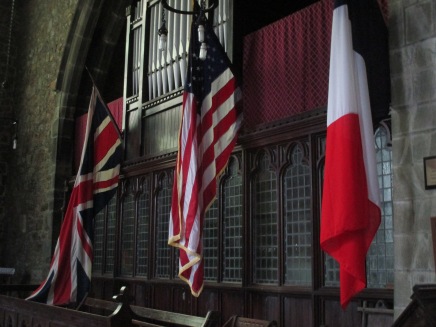

Three flags hang in the chancel: alongside the Union Jack are the French Tricolore and the Stars and Stripes. Poignant reminders.

I’m glad we saw Princetown on a dour, damp, glowering January day. And I’d happily go back again – though perhaps in the summer next time.

Information and old photos are from these sites:

http://www.legendarydartmoor.co.uk/prince_church.htm

http://www.dartmoor-prison.co.uk/history_of_dartmoor_prison.php

https://oldprincetown.weebly.com/princetown-church.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sabine_Baring-Gould

I read a few of the good man’s books in my days researching medieval hagiography, but he wrote some fascinating amateur histories on folkoric topics like werewolves. Princetown is pretty grim, whenever I’ve been there. My grandchildren were freaked out when they were little by the prison building and refused to go near it. I’d bet even the Baskerville hound would baulk at it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hope to find a few more of his works over time, Simon: such an eclectic range of interests! I know what you mean about the prison. I wanted to take a photo of the entrance but didn’t dare!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have had nightmares since childhood after reading The Hound of the Baskervilles and a cold chill ran down my back reading that excerpt about bogs on the moors!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m sure it’s perfectly safe really, Rose; I just like to ramp up the drama! Then I read the Reverend’s words… Gulp! 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, I had never heard of the reverend, it seems like an interesting place to visit, if we ever get back to that area again. That postcard of Princetown Church shows so clearly where the unmarked graves are.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, the postcard is telling. I think you would enjoy visiting this church.

LikeLike

So well worth saving such an excellent post

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Derrick! That makes me feel better 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I couldn’t figure out why the Reverend’s name sounded so familiar–I read The Moor, that’s why! He does sound like a fascinating man. I loved Dartmoor (though we were there in better weather!) but I didn’t go to the church or prison. Next visit!

LikeLiked by 1 person

There can’t be many with a name like his, Kerry!

LikeLike

Thank you – I’ve been wondering about whether to read Baring-Gould for a long time and this was just the push I needed. The Man of the House spent some of his childhood in Princetown when his father was a prison officer and has told me many tales of that time and of the history. We went back a few years ago but don’t feel the need to go again, but we will definitely go back to the surrounding countryside.

LikeLiked by 1 person

How interesting that The Man of the House is from Princetown! I found such a unique place. LIke you though, I don’t feel the need to return, unless B takes a fancy to try the museum again in which case we’ll go in summer.

I loved A History of Dartmoor, Jane: to skim through more than read closely, and also because I had an old book in my hands which is always such a treat. He wrote a great deal, of course, including specifically on Cornwall, so I shall find more of his work in time. This one will be back in the library system early next week – ready and waiting for you!

LikeLike

What a fascinating story. So much of our 19th century architectural history seems to have been built thanks to prisoners, or to the philanthropy of landowners seeking work for unemployed men in their community without any other means to support their families. Yet another reason to visit Dartmoor (I’m reading your posts in the wrong order …)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Philanthropic building projects I was aware of, but I’d really not encountered the idea of prisoners building before this. It makes obvious sense of course. To finance and build the church, only for it to close … almost as short-sighted as some of our more current projects 😉

LikeLike

Sadly, as a greedy and lazy reader, I have a copy of his annotated Sherlock Holmes on a shelf here! I must read it!

xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh please do! And let me know how you find it 🙂 x

LikeLike

Fascinating history and a most delicious description of a bog! I can just imagine myself sinking into it and feel the cold, muddy water seeping over the top of my boots … what makes you think this has happened to me …

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well… knowing the area you live in, I can imagine there’s a bog or two in the neighbourhood…

LikeLike